A map is a catalog of queries and clues—not only about location and distance but history. Maps of North America pose a question many an onlooker cannot answer: Why is Alaska part of the United States of America and not of Canada—or, for that matter, of Russia?

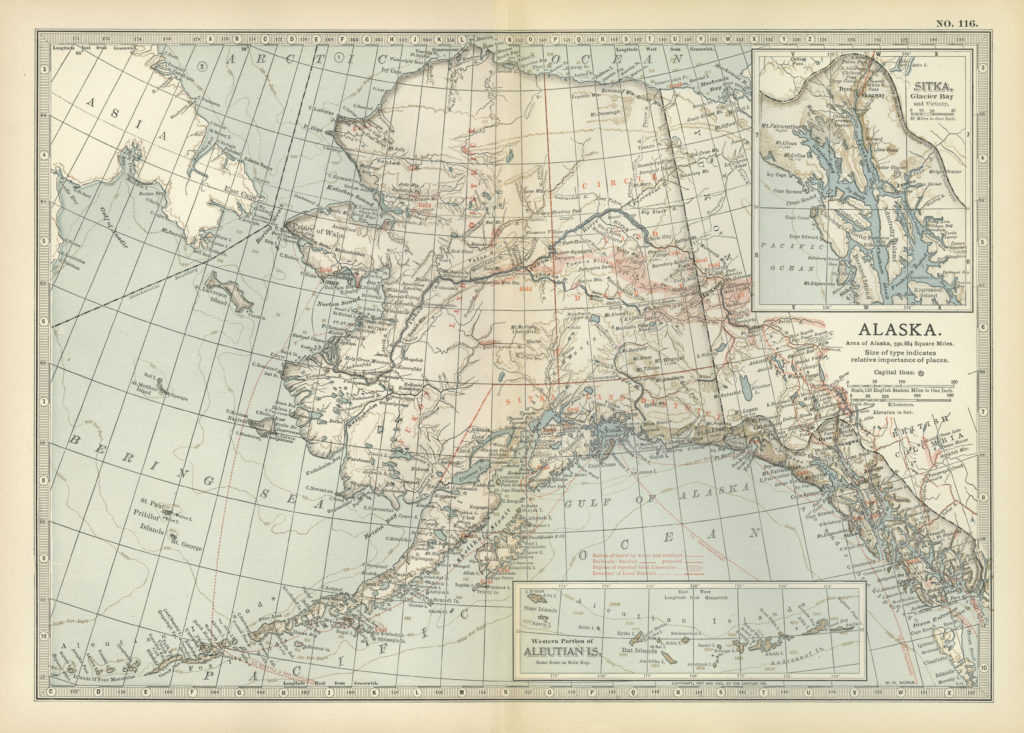

The short answer is that the United States bought Alaska from Russia in 1867. But geography appears to confound the logic of that sale. The largest state lies only 55 miles across the Bering Strait from Russia and shares a 1,538-mile eastern border with Canada. In addition, Alaska’s southernmost town, Ketchikan, is 608 miles north of Bellingham, Washington, the nearest city in the Lower 48. How did Alaska’s 663,268 square miles wind up in the United States and not another country?

The answer lies in the longstanding rivalry between Russian traders and Britain’s commercial stand-in, the Hudson Bay Company, over the riches offered by the fur trade, leading to a fierce and bloody battle prompting Russian explorer Alexander Baranov to claim what became Sitka, Alaska.

On September 29, 1804, Katlian, war chief of the Sitkan Tlingit, was standing atop a rocky promontory near his village, on the shore of southeast Alaska. His vantage point offered a view of a harbor choked with hundreds of baidarka, the indigenous watercraft Europeans came to call kayaks.

The Sitkan Tlingit, like the rest of their tribe, were a combative maritime people, animists whose shamans exerted strong influence and whose warriors fought masked as animals, their bodies painted red, white, and black. Like the Polynesians of the South Pacific, Tlingit sailed the open seas in highly decorated canoes, often more than 70 feet long. A hundred warriors, armed with clubs, daggers, spears, bows and arrows, could fit aboard. In raids along the Pacific Northwest coast, Tlingit marauders struck village upon village, enslaving those they did not kill and earning enmity that had perpetuated centuries of violence. However, Katlian was on the lookout not for other natives, but for Russians—in particular, Alexander Baranov.

In 1741, Russia had claimed Alaska as a colony, sending explorers to probe the enormous region and hunters to bring back furs, among the most valuable commodities of the day. Fur trading companies like Golikov Shelikov eked out marginal profits amid fierce competition from other Russian businesses and the challenges of surviving in the Arctic and sub-Arctic wilderness with minimal support from Russia’s government. Russian colonists treated Tlingit and other native peoples cruelly, prompting retaliation.

Russian trappers controlled the Aleutian Islands, the peninsula leading to them, and Kodiak, an island just off the mainland. That area’s natives—Aleuts, Alutiiqs, and Athabaskans—allied with the Russians out of intimidation by the colonizers and desire for the economic advantages over rival tribes that the Russians provided.

In 1799, Czar Alexander consolidated Russian fur companies in Alaska into a single entity, Russian American Company, which resembled the Hudson’s Bay Company, a quasi-governmental presence in English-controlled Canada. Besides turning a profit, Russian American Company duties included keeping foreigners out of Alaskan waters and preventing the native population from trading with the Hudson’s Bay Company and other international rivals.

Russian American Company had enriched and elevated Alexander Baranov. In the 1780s a clerk at a store outside Moscow, Baranov caught fur-trading fever, spurring him to abandon his wife and daughter for Siberia. With borrowed money he bought guns to swap for the furs of animals trapped by the indigenous Chukchi, who lived along the Bering Sea and were a Russian variant on the Tlingit 55 miles east. Soon after Baranov arrived in Siberia, Chukchi bandits robbed him of his stake. In 1791, hounded by creditors, Baranov took a job no one else wanted as Golikov Shelikov’s manager at Kodiak Island, on Alaska’s south coast. En route, a storm destroyed his ship.

Once at Kodiak, though, the frail-looking Baranov proved an indomitable whirlwind. He saw to the construction of a town he named for the island and to the building of the first sailing ship to have a keel laid on North America’s Pacific coast. He led fleets of baidarka against those of competitors, illegally deporting rival companies’ employees in chains, ostensibly for mistreating natives. Baranov also struck deals with the captains of American ships working the waters around Kodiak. His men would help the Yankees gather otter pelts that the Americans would sell in China, splitting the profits with Shelikov. The arrangement put Baranov in the black every year, pleasing his masters.

But the south coast’s sea otter population was dwindling. In 1795, seeking richer trapping grounds, Baranov—dogged by the Hudson’s Bay Company—explored unclaimed southeast Alaska, 1,000 miles southeast of Kodiak and heretofore left to the warlike Tlingit. Baranov and his men found otters galore, but also Tlingit using British trade goods and carrying British muskets. To counter the Hudson’s Bay Company’s influence, Baranov decided to establish a settlement. He negotiated with Tlingit to buy a site off Sitka Sound, seven miles north of Sheen Atika, a village inhabited by the Kiks.adi Tlingit. Typical of its kind, Sheen Atika consisted of brightly painted longhouses and elaborately carved and decorated totem poles. Beyond Sheen Atika loomed the nearly impenetrable Tongass rain forest.

After buying the land, located along historic sea routes, Baranov returned to Kodiak and began peppering the southeast Alaskan mainland with Russian outposts. In 1799, based on his reputation for efficiency and profits, the czar appointed Baranov governor general of the reorganized Russia America colony and general manager of the newly created Russian American Company.

On July 7, 1799, Baranov returned to Sheen Atika with 100 Russians, 700 Aleuts, and 300 Athabaskans. He and his men set about building what he called Redoubt Saint Michael, named for a beloved pillar of Russian Orthodoxy. By winter the work force had erected a warehouse, a blacksmith shop, barracks, blockhouse, and living quarters for hunters. That spring Baranov sailed to Kodiak, leaving 25 Russians and 55 Aleuts.

The Russian American Company was taking 75 percent of its otter pelts in and around Sitka Sound, but relations between the Russians and the Kiks.adi—and the Tlingit in general—had soured. Arrogant and demanding, Russians were taking Tlingit women as concubines and competing with Tlingit hunters for game. Other Tlingit clans were taunting the Kiks.adi for being slaves to the interlopers. During the winter of 1801, clans assembled on Admiralty Island, near what is now Juneau, to discuss the Russian problem. The parley included Hudson’s Bay Company men, who offered firearms, powder, and ammunition. The Tlingit decided to eliminate Redoubt Saint Michael, which by 1802 was home to 29 Russians, 200 Aleuts, a few Alutiiq Kodiak women, and three Britons who had deserted from passing ships.

In June 1802, reinforced by warriors from neighboring clans, chiefs Katlian and Skautlelt led a strike against Saint Michael. In the attack, Katlian grabbed a blacksmith’s hammer; in his hands, its heft and mass made it more weapon than tool. Putting the settlement and an unfinished ship to the torch, the Tlingit looted the Russians’ cache of pelts and killed most inhabitants. Only three Russians and 20 Aleuts survived, to be rescued by a British sea captain who ransomed them at Kodiak for 10,000 rubles. The attack devastated Russian American Company revenues and so rocked the Pacific Rim that 2,800 miles to the south Hawaiian king and Russian trading partner Kamehameha proposed to send warriors to aid the Russians in retaking the settlement and punishing the raiders. Baranov rejected Kamehameha’s offer. He meant to make recapture a Russian-American affair, and to re-establish the company in southeast Alaska.

At Sheen Atika, Kiks.adi shaman Stoonook was riling fellow villagers. Stoonook described visions he had had of a vengeance-minded Russian coming for them all. His warnings persuaded the Kiks.adi to build a fort. War chief Katlian selected a site south of the village, adjoining the Indian River and bounded by tidelands so shallow that the structure would be secure even from naval cannon fire. Katlian also cached gunpowder a canoe trip away. Meant as a fallback in case Stoonook’s vision came true, the fort consisted of a thick spruce palisade—the Tlingit hoped the green logs would deflect cannonballs—enclosing 14 buildings. When the Kiks.adi had attacked Saint Michael in 1802, other Tlingit sent men. This time other clans held back, but Hudson’s Bay Company men promised to supply weapons, and also to keep an eye out for Russians.

For days, as Baranov’s fleet crawled the southeast Alaskan shore, British and Tlingit scouts monitored the invaders until their 250 baidarka, carrying 150 Russians and 450 Aleut fighters, came into view from the promontory where Katlian had been keeping watch. His warriors painted their bodies white, blue, maroon, and black and donned their animal masks—Katlian, with his war hammer, would fight in the guise of a raven.

The Tlingit did not know that as Baranov’s flotilla was paddling out of Pearl Strait into Sitka Sound, the Russian war sloop Neva appeared. Commanded by Yuri Lisyanksy, the 200-foot Neva was conducting Russia’s first global tour. Lisyanksy had paid a courtesy call at Kodiak just after Baranov’s punitive force departed. Learning of the governor’s plan, Lisyansky made straight for Sheen Atika, catching Baranov as he was about to attack. The 43-man Neva had 14 cannon and three patrol vessels, dramatically enlarging Baranov’s power.

Emboldened, Baranov landed under a flag of truce at a deserted Sheen Atika; the villagers were withdrawing south to the palisaded fort. Baranov sent runners to Katlian at the fort with an offer to pay a second time for the land on which Redoubt Saint Michael had stood. Feigning interest, Katlian stalled while his people made it into the fort, meanwhile sending men for the powder cache. Neva crewmen noticed those movements and alerted Baranov, who deployed riflemen. As a canoe of Tlingit carrying the powder landed, a Russian round set off a blast that killed all hands.

The next day Aleuts rowing lifeboats from the Neva towed the warship into the Indian River shallows, less than a mile from the Tlingit defenses. Under covering fire from the sloop, Baranov landed 150 men and four of the ship’s small cannons. The governor split his force, leading a column of Aleuts against the fort. The defenders loosed a musket barrage so intense the Aleuts ran for their baidarka. Baranov mustered Russian trappers to retrieve the abandoned cannons.

Swinging his hammer like a mace, the raven-faced Katlian led a charge from the fort. The force he had positioned across the Indian River also attacked. The Tlingit pincer caught the enemy as if in a vise, with Russians using hunting knives and flintlocks to fight hand-to-hand against Tlingit daggers, spears, and clubs. The Tlingit were driving the Russians toward the waterline when Baranov fell with a chest wound. His companions, with 12 dead and 26 wounded, crouched among boulders around their leader. From the Neva, Lisyansky fired cannon rounds to scant effect, then dispatched a rescue squad to retrieve survivors. A doctor went to work treating the governor’s wounds. Only after dark were Russians able to slip ashore and retrieve their cannons.

Through the night the Tlingit celebrated. Taunting the enemy with chants, the Indians dangled a headless, arrow-riddled Russian corpse from their palisade. Taking command, Lisyanksy had his little fleet bombard the Tlingit fort, again to no effect. Gangs went ashore to fell trees and fashion rafts on which to float cannon and cannoneers nearer the native redoubt. By early afternoon, Russian gunners still had not breached the fort walls. Lisyansky sent a man to demand surrender, triggering a roar of laughter. Katlian said the Russians should surrender. The bombardment resumed until nightfall. In darkness, the Tlingit discussed strategy. Powder was in short supply. Other clans would not help them. The Indians decided to withdraw north to the site of a long-dormant village and escape into the Tongass.

At daylight, Lisyansky found Katlian seemingly willing to discuss terms. The Russian offered a truce, along with a hostage exchange and further talks. The chief dithered while elders prepared the Tlingit to march to Pearl Strait from which they would canoe to another island and then reach the forest. The day proceeded in a stutter of cannon fire and truce talks. Finally the clan proclaimed that its members would come out of the fort in the morning. That night the attackers heard a lengthy Tlingit song, followed by a drum roll and screams, from the fort. Lisyansky thought he was hearing the Tlingit agonize about surrendering. The morning of October 7 the Russians entered the palisade to encounter a scene from a slaughterhouse. “Numbers of young children lying together murdered, lest their cries should have led to a discovery of the retreat,” Lisyansky wrote. A rear guard of Tlingit warriors killed eight Aleut trappers at Jamestown Bay and another Aleut outside Sheen Akita. Considering the ominous shadows of the Tongass, the Russians declined further pursuit.

Baranov had his Aleuts bury the infants en masse, sent off with an Orthodox priest’s prayers. He led his men back into Sheen Akita, renaming the village New Archangel, after the European Russian city of Archangelsk on the White Sea. The governor stood at the heart of the village as his men looted its remnants. “Burn the damn place!” Baranov roared. By dusk the long houses and totem poles were an inferno.

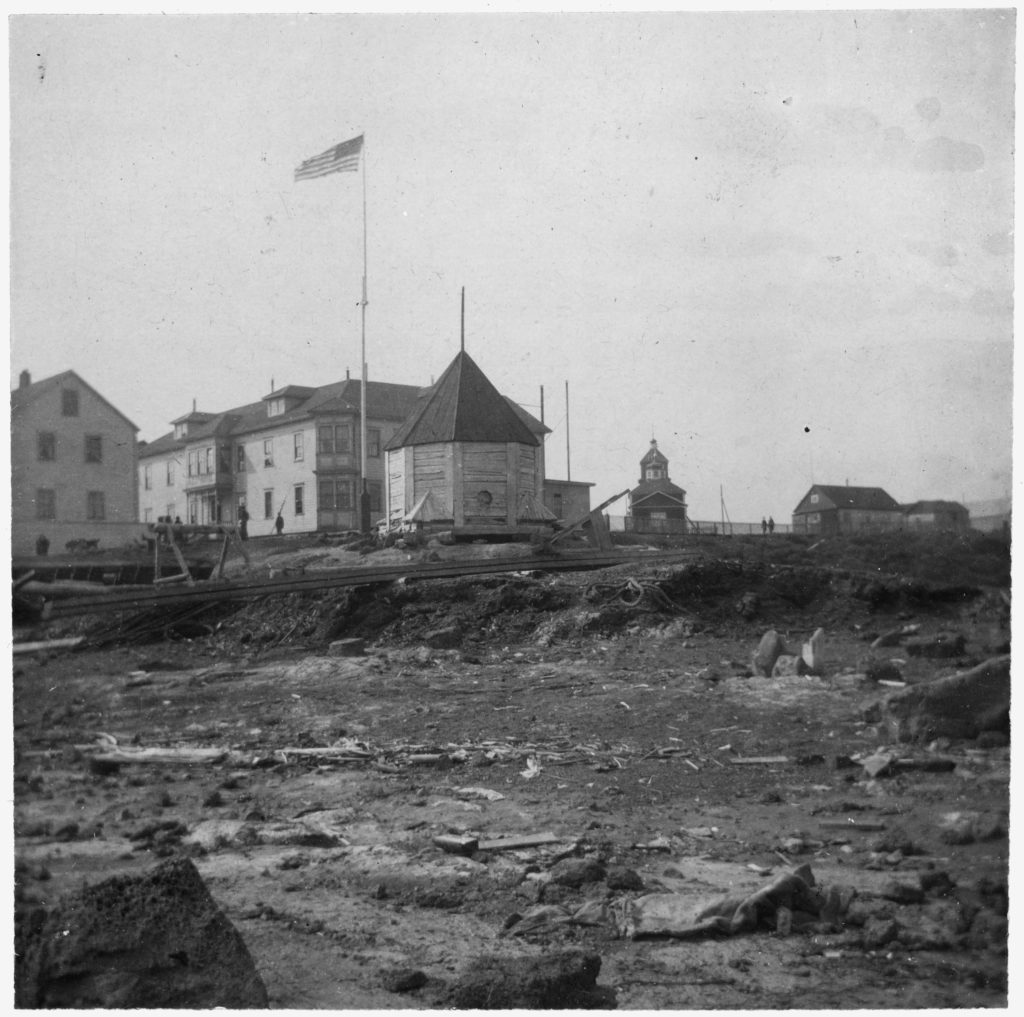

To deny the Tlingit reuse of their blood-soaked fort, men from the Russian force dismantled the palisade and its contents, also laying a foundation for a government house, in time called Baranov’s Castle, atop the promontory. Lest the Tlingit attack, the Neva stayed on until November, warding off the natives and reinforcing demands by Baranov that Hudson’s Bay men leave southeast Alaska. Baranov surrounded New Archangel with a palisade incorporating three watchtowers mounting 32 cannon. The settlement soon was outdoing Kodiak at producing revenue from furs. Baranov built an observatory and the first school in North America to educate whites and natives together. The governor’s international stature grew when in 1806 he engineered the return to Japan of fishermen shipwrecked the year before after being blown off course.

By 1805, Moscow’s newest outpost in North America had attracted visits from more than 200 exploratory expeditions representing Russia, Britain, France, Spain, and the United States. In 1808, Baranov moved the capital of Russian America from Kodiak to New Archangel. Russian dependence on grains prompted Baranov to mount expeditions southward. In 1812, at a northern coastal district of Spanish-ruled California, he founded Fort Ross—“Ross” is the anglophone corruption of “Rossiya,” or “Russia”)—near what is now Jenner, California, as an entrepot for getting grain products to Russian America. In 1809, the czarist government transferred Asia’s Kurile Islands and the Kamchatka peninsula to Russian America’s jurisdiction, making the North Pacific’s coasts a Russian holding, with Baranov its ruler and New Archangel its capital.

Baranov instigated his own downfall by overreaching. In 1817, thinking to advance his hegemony, he sent a force to seize Kauai, Hawaii, from King Kamehameha. At Kauai, the Russians built three sets of fortifications, the largest called Fort Elisabeth, to prop up a local figurehead as “king of Kauai.” Kamehameha counterattacked, sending the invaders fleeing back to Alaska. The czar, who wanted friendship with Hawaii, jerked Baranov out of his post. In March 1819, the disgraced former governor general was sailing back to Russia when he died off Java.

Baranov was Russian America’s last profit-minded civilian governor; his successors were military men disinclined to make money. Russian Alaska shrank when the government reassigned the Kuriles and California to other departments. In 1824, Russia allowed the Hudson’s Bay Company to pursue the fur trade in southeast Alaska. Relations with the Tlingit simmered, sometimes boiling over.

Losing a war over Crimea to England in 1854 and an 1858 Tlingit attack on Sitka stopped only by point-blank cannonades, the czarist government decided to sell its North American colony, offering it to the United State in 1859.When the American Civil War intervened, the czar briefly toyed with private investors from California before selling the gigantic region, in which Russia had never settled more than 400 people, to the United States for $7.2 million. The deal was consummated in 1867 on the watch of U.S. Secretary of State William Seward. The considerable price, wariness of imperial expansion, and tensions with the Tlingit led cynics to term the arrangement “Seward’s Folly”; the Senate approved the purchase by only one vote. The change of ownership meant nothing to the Tlingit; as late as 1877 the tribe was besieging Sitka. Not until an 1880 gold rush at Juneau and a subsequent influx of Christian missionaries were the Americans able to pacify the tribe, whose doughty stand outside Sheen Atika helped bring about their—and their homeland’s— incorporation into the United States of America rather than into Russia or Canada.